WTFhappenedin1971.com is a fantastic website, replete with all sorts of graphs showcasing the various ways that society has declined since then. Here are some of my favourites:

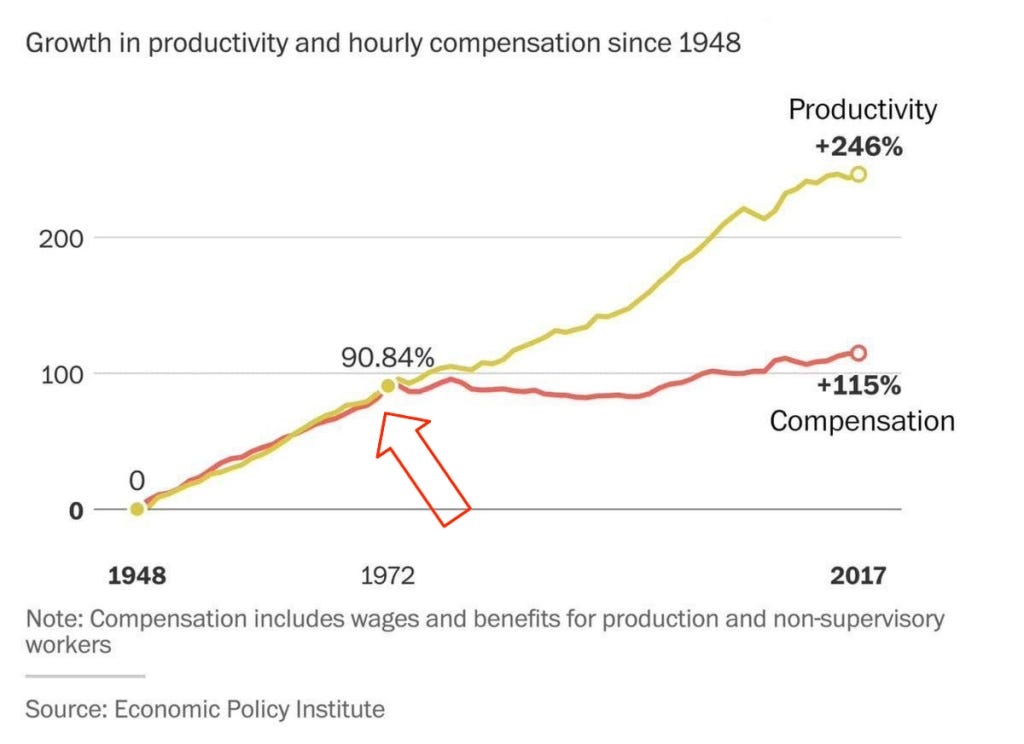

Average compensation plateaus whilst productivity continues to rise (1948-2017)

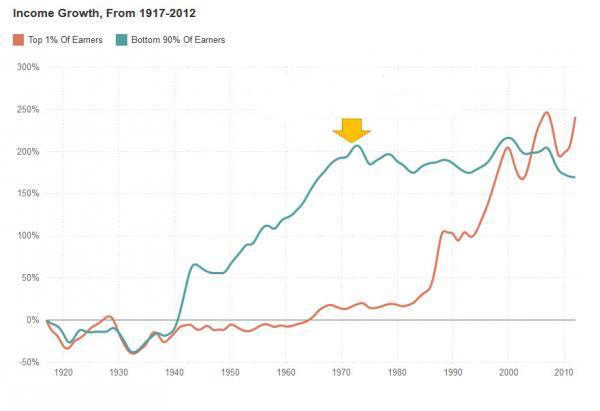

Comparing income growth of the top 1% with the bottom 90% (1910-2010)

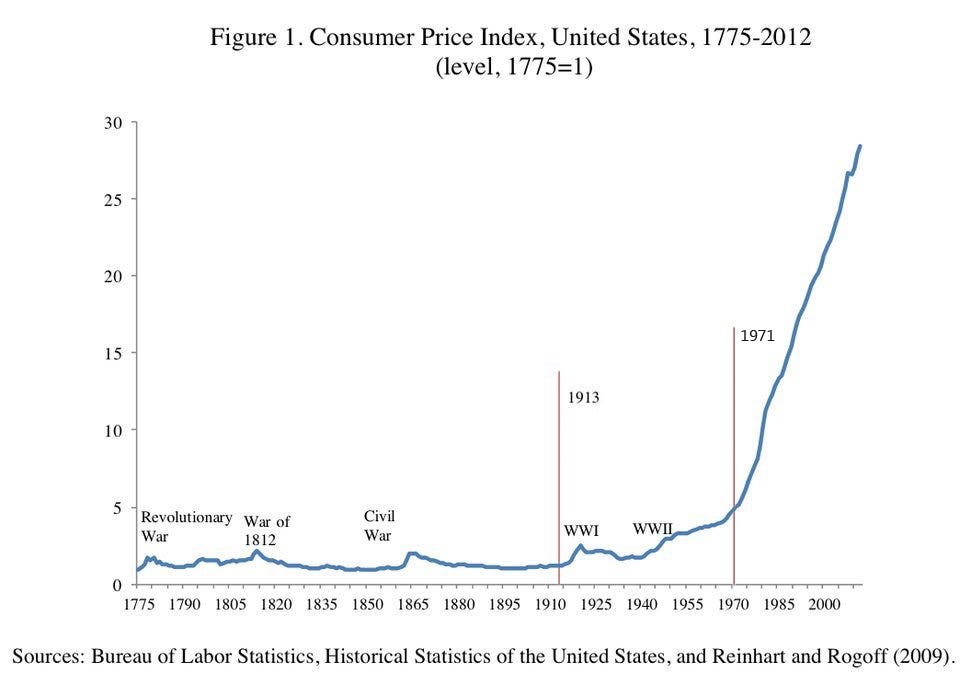

US CPI (1775 to 2012)

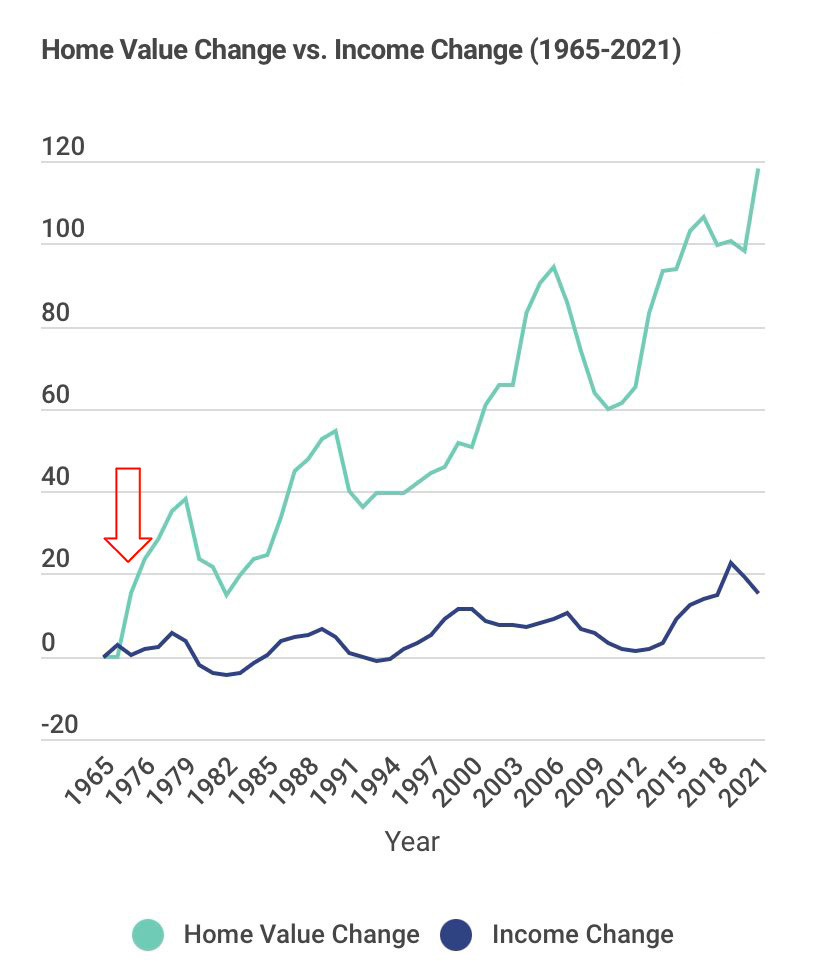

Change in prices of homes vs change in income (1965-2021)

Lawyers per 1,000 people (1850-2010)

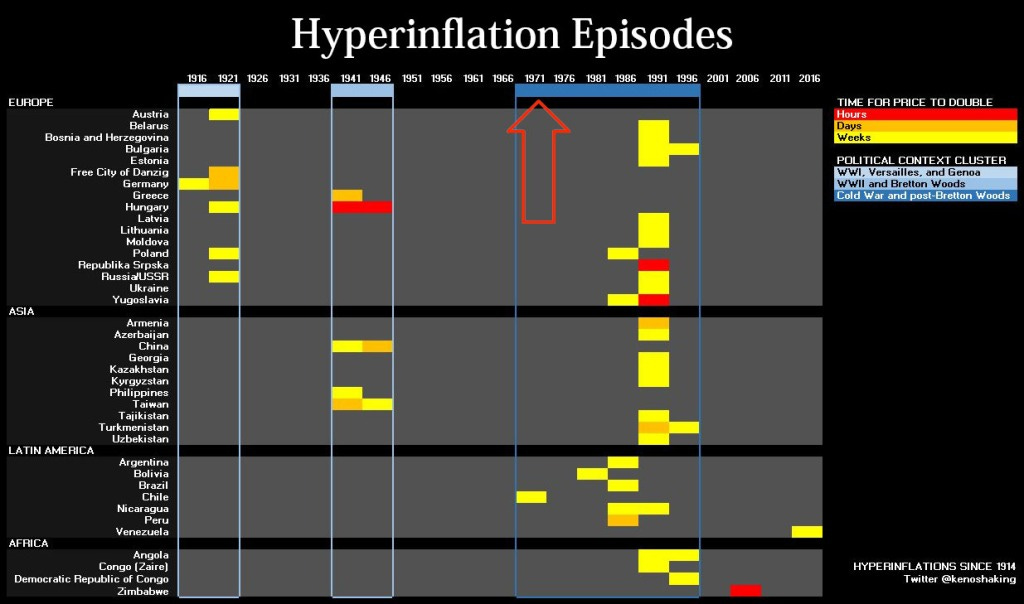

Hyperinflation episodes (1916-2016) 1

So… what did happen in 1971? Quite a lot: Justin Trudeau was born, Hunter S. Thompson published Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Klaus Schwab founded the WEF, and Led Zeppelin released Stairway to Heaven. But are these things really enough to trigger a wave of hyperinflationary episodes, create a far more litigious society, and exacerbate wealth and income inequality? Surely Trudeau can’t be that bad?

“The idea that "a little" inflation is a good thing is not much unlike the idea that "a little" sloppy coding is a good thing. After all, if people wrote good code how'd all the various "experts", antivirus makers etc all pay their mortgages ? Not too much sloppy code, so whatever software we're trying to write sorta works, but a little, to ensure that we're never going anywhere with it. Pretty insane, wouldn't you say ?”

— Popescu

By far the most consequential development in 1971 was the end of the Bretton Woods system. Established in 1944, the Bretton Woods system established a new order whereby many currencies around the world were pegged to the dollar, which was in turn redeemable for gold at a fixed rate of $35/oz. The system was designed to provide international stability and to facilitate trade after WW2, but by the 1960s the international community was starting to lose faith in the dollar. The Vietnam War had required the USG to print more dollars than their gold reserves could support; as the government printed more money, countries around the world became concerned that they wouldn’t be able to redeem their dollars for gold.

French President Charles de Gaulle, who was one of the most vocal critics of Bretton Woods, started to convert France’s dollar reserves to gold and beginning the process of repatriation. To exemplify France’s lack of faith in the US and her financial stability, De Gaulle sent the warship Colbert to New York in 1965 to transport the gold. This was symbolic, and other countries began their own processes of repatriation.

This meant that President Nixon had a dilemma: would he allow foreign countries to continue to convert their dollars to gold, thus potentially depleting the US’s gold reserves? Or would he suspend the convertibility of dollars to gold? He opted for the latter, and in August 1971 Nixon took the USD (and all currencies pegged to the USD) off the gold standard.

The results speak for themselves. The state has grown into an extortion racket leeching off the private sector like a parasite, whittling out the middle class via the Cantillon Effect. Whatever survives on the other side of a monetary reset will do so in spite of the government myopia and heavy-handedness, and not thanks to the ingenuity of the public sector.

“The state is an institution of organised violence that benefits a few at the expense of the many.”

— Erik Voorhees

If a society is predicated on the notion that a small number of central planners can make decisions for the masses, it will deteriorate quickly. Chris Whitty’s spreadsheets, Matt Hancock’s shamelessness, the Labour Party’s masochistic desire for national self-flagellation and incompetent wokerati are a stain on the UK, causing the ambitious segments of society to recoil in horror — and in many cases just leave the country. Such is the essence of Keynesian indoctrination: the idea that decisions of individuals can be efficiently and predictably discounted, and that the masses will therefore do better when managed by a helicopter nanny state.

Most concerningly, the time since 1971 marked a shift away from family and community, in favour of deferring decision-making to the state; it marked a shift away from people taking personal responsibility and accountability, and instead this responsibility was bestowed upon the very last people that can be trusted. This inversion of incentives fractures and fragments society, as opportunists start to take liberties. Some of the best examples of these are encapsulated by the 2009 Expenses Scandal, where it was discovered the extent to which MPs were milking the electorate to splash on their personal lives. Some entertaining examples include Sir Peter Viggers’ expenses claim to build a floating duck house in his garden pond, Douglas Hogg’s claim for cleaning the moat around his country estate, Michael Gove’s claims for buying luxury furniture for his home, and the £20,000 David McLean spent renovating his stables. The current Labour government behaves in exactly the same way as their predecessors, except that they are more overt and less apologetic. In the US, there have been some far more serious examples: on September 10th 2001, the day before 9/11, the US Secretary of Defence, Donald Rumsfeld, announced that the Pentagon could not account for $2.3 trillion in missing funds. If I lent someone £50 and they immediately lost it, I’d think twice about lending to them again — in this instance, it took 16 years before a full audit of the Pentagon was first conducted in 2017. In the six subsequent years the Pentagon failed every single full audit it has undergone, and the most recent audit showed that of their $3.8 trillion in assets, half did not meet accounting standards.

As the base layer of energy transmission in any society, having a corrupt form of money ripples out and damages every other layer of a nation — this goes far beyond financial implications. It doesn’t strike me as a coincidence that modern art is a load of tosh when the state allocates capital so profligately; resources will always be poorly-allocated when there’s scant reliability in the value of each currency unit, particularly by those who are spending others’ funds.

When surrendering control of money to the state, there are serious ramifications: to what extent does art lose subjectivity if Westminster appoints itself Chief Patron of the Arts? Not only does it taint the perception of art itself, but why should taxpayers be funding conceptual and subjective art, such as the Tate’s acquisition of Tracey Emin’s unmade bed, replete with condoms and dirty sheets, which it acquired for £2.5m? If the Tate’s board of trustees (who have been known to use government funding to buy their own art from themselves) weren’t looting the public purse for laughs, we’d have a more respectable society. Unfortunately, there’s no real incentive to change the status quo when the currency itself is magicked up by the printing press in Andrew Bailey’s basement.

Governments, financed by a class of central banking terrorists, are the worst people to manage money, and are never held accountable for their inexplicable incompetence. Most civilised capitalist societies oppose price controls and over zealous central planning: for example, we don’t have a committee controlling the prices of potatoes, lest there be shortages. So why do we centrally plan the money? In particular, why do we continue to centrally plan our fiat currencies (“fiat” literally meaning “by command/decree” in Latin) when every single government does the same thing: steal from the the citizenry by devaluing their savings. How long can people put up with this before Guy Fawkes becomes the national hero once more?

WTF happened in 1871?

In 1871, 100 years before the end of Bretton Woods, several countries around the world experienced quite the opposite: a sustained period of deflation on a gold standard.

Keynesian doctrine often conflates deflationary growth with deflationary crises. The central bankers who witter on about how “2% inflation is ideal” are talking rubbish. In a true free market, prices fall to the marginal cost of production, which means that goods and services ought to be deflationary. I’ve written about this before, but the phenomenon is best explained by Jeff Booth’s Finding Signal in a Noisy World.

Deflationary growth is fantastic: as more goods and services are produced more easily and more efficiently, prices fall and standards of living rise commensurately. Deflationary crises, by contrast, are symptomatic of debt-based systems: prices may fall, but only because the currency itself was overextended.

After the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), Germany demanded reparations from France in gold, and also moved to adopt its own gold standard from 1871-1873. This increased demand for gold meant that prices denominated in gold fell. In the subsequent years technological advancements such as railways and steamships fostered huge boosts in productivity, causing prices of goods and services to consistently fall year on year. This became known as The Long Depression, a period in which prices continued to fall.

The UK experienced its golden age from 1871-1914, and built some of the world’s best architecture during this period. Waddesdon Manor, Sandringham House, Cliveden House, Dunrobin Castle, Knebworth House, Tyntesfield, Polesden Lacey, Leeds Castle, The Natural History Museum, The Royal Courts of Justice, Tower Bridge, and The Midland Grand Hotel were all built during this period. I’d contend the reason we don’t build such fantastic buildings nowadays is inextricably linked with the fact that soft money shortens time preference, thus forcing people, companies, foundations and governments to discount the future in favour of the short term — in other words, if you don’t spend myopically, you are punished for it. On a fiat standard, you therefore cannot afford to undertake such large-scale long-term construction projects, because the capital that you fund it with depreciates too fast.

It was also a time of huge breakthroughs in chemistry, aerodynamics, social sciences, thermodynamics, exploration, antiseptics, electromagnetism, and evolutionary biology.

According to Saifedean Ammous, the reason that society was so productive during this era was because the fiscal constraints imposed by a gold standard fostered a far more productive economic environment: when the state attempts to remove opportunity cost (however illusory this may be), resources are more likely to be squandered on nonsense.

Not all countries experienced this same degree of prosperity after 1871, particularly those who were still fully dependent on a silver standard (I’d recommend Dominic Frisby’s article for more on this). Throughout the 19th century, many countries either pivoted from a silver standard or a bimetallic standard to a gold standard (the pivot started a lot earlier in the UK, thanks to decisions made by Sir Isaac Newton in 1696 and 1717 whilst Master of the Mint at the Bank of England). However, some countries still based their economies on a silver standard, and suffered because of it. The most notable example was China, which operated fully on a silver standard until 1935. China’s economy suffered from the fluctuations between the silver and gold prices, and particularly the fact that silver depreciated significantly against gold: in 1871, the ratio of gold:silver was roughly 15:1, but by 1933 this ratio had fallen to 80:1.

A return to “hard” money

It is inevitable that the current system will collapse: it is just a question of when it will happen. The US national debt currently stands at $35 trillion, about ~124% of GDP, and most other Western countries are similarly indebted.

Our overlords at the Federal Reserve, Bank of England (BoE), European Central Bank (ECB), International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Bank for International Settlements (BIS) have concocted some badly thought out plans to prepare for this.

Some have posited that we return to a gold standard. This is unlikely to happen for several reasons, not least of which that nobody really knows how much gold anyone else has, and there is no way to feasibly prove it. The last full audit of the US gold reserves at Fort Knox happened in 1953! Can the Chinese really trust the Americans that they have the gold they claim to? By contrast, could the anyone trust that the Chinese have the gold they claim to?

2020 was a tumultuous time, and in a little-known city called Wuhan, one of the largest gold-related scams of all time unfolded (who knew Wuhan was such an interesting place?). Kingold Jewellery Inc. took on loans amounting to 20 billion yuan (~$2.8bn) from various Chinese banks, and then promptly defaulted on their loans. When the banks tried to liquidate the 83 tonnes of gold bars that had been posted as collateral, it was discovered that the gold was fake: the bars in question were actually just gold-plated copper. To contextualise the scale of the issue: the 87 tonnes of gold would have equated to about ~4% of the amount of gold held in the country’s national reserves, raising questions about how much the Chinese can be trusted to accurately count their gold.

Others have been putting plans together for Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs), in order to repackage the current financial system but with enhanced surveillance and eroded freedoms — the technical term for this is “putting lipstick on a pig”. With ambitious statements from the likes of the BIS and ECB, it seemed that CBDCs were closing in on us quickly. After Sunak’s speech about the British CBDC, Britcoin (the name suggesting they already know they’ve lost), it seemed as though tyranny was just over the horizon. However, there have been some significant developments in this regard over the past few months, not least of which being the revelation that governments and central banks are totally unprepared to implement these. Also, to do so would be political suicide. In the US, The House of Representatives has already passed a bill which prevents the Federal Reserve from releasing a CBDC. On a smaller scale, the Mayor of Florida, Ron DeSantis, has pushed legislation to protect Floridians from a CBDC, and to make their implementation illegal.

Rising nation state adoption of bitcoin

Similar to the way in which global supply of gold was constrained relative to goods and services in the years after 1871, the same is happening today with bitcoin. In 2021 El Salvador made bitcoin legal tender, and this triggered a lot of optimism that other nation states would follow suit, either by making bitcoin de facto legal tender, or simply disbanding legal tender laws altogether, Milei style. Instead, there was a feeble attempt at adoption by the Central African Republic, and rumours that the planned adoption in Guatemala and Honduras had been quashed by the US authorities (the so-called “economic hitmen”). The circular economies that have been built up over the last few years have largely been devoid of top-down state involvement, such as those flourishing across Central and South America, in countries like Nigeria (where the eNaira CBDC failed spectacularly), and even in wealthier areas that don’t need bitcoin as a lifeline, like Lugano in Switzerland.

However, this isn’t to say that governments around the world haven’t inadvertently found themselves with significant bitcoin holdings. As of today, the states with the largest publicly-disclosed bitcoin holdings are (in order): the US, China, the UK, Bhutan and El Salvador. Germany fell off the list earlier this year, as did the Bulgaria a few years earlier (which at one point held ~213,519), but attitudes towards the asset have changed. This year, in particular, has been remarkable for the extent to which politicians have begun to approach bitcoin differently. In July, Donald Trump professed that, as President, the USG would hold onto all of their BTC and use it as a strategic reserve — he has even entertained the idea of using bitcoin to pay off the US’s national debt (making him one of the only politicians in the West to even address the issue). The Kingdom of Bhutan recently exposed their holdings: the country appears to have accumulated over 13k bitcoin through Druk Holdings, the government’s investment arm which makes use of Bhutan’s natural resources to mine bitcoin cheaply. Bhutan’s holdings have grown significantly, and are now worth roughly one third of the country’s GDP.

Since inception, bitcoin has risen from being completely worthless to roughly ~0.1% of the global wealth (~$900 trillion). This is phenomenal growth, but there’s plenty of room left to grow, particularly given how sluggish and lethargic the incumbent monetary systems have become. So, even though things may seem bleak at the moment (and things can definitely get worse in the short term), I’m extremely optimistic about the future. Not because I believe governments will learn fiscal responsibility, but because bitcoin reintroduces opportunity cost: those governments who don’t adapt will find themselves lost in No Man’s Land, now that people can opt out of their monetary tyranny.

Bitcoin is the best shot society has at returning to a hard money, and the glory days post-1871, when the prices of goods and services fell each year, rather than rising. It will invert the post-1971 Keynesianism experiment of fake money, and we’ll be all the more prosperous for it. I’ve no idea how long this will take, but I see the process as inevitable: if governments wanted to shut it down, they had to act before ~2014 — since then, the hash rate since has simply grown too much for any nation to dominate (now at almost 700,000,000 TH/s). The following quote from Popescu (I’ve shared it before) summarises my view on this inevitability quite nicely:

“There is a reason Bitcoin will crush fiat. It's not the bursting of the inflationary bubble, even if that alone would be enough. It's not the solving of the otherwise unresolvable security problem of fiat banking, even if that alone would also be enough.

It's simply that in any competition between two systems, the one that preserves property rights will completely crush the one that does not. This isn't for any ideological reason, it isn't because "the people" like it more or trust it more or prefer it or anything of that kind. The people don't even enter into the discussion at all. The system which doesn't preserve property rights is less of a system, and consequently doesn't have a prayer.”

It’s a shame this chart stops at 2016. Since then, the following countries have experienced hyperinflation: Venezuela, Zimbabwe, South Sudan, Sudan, and Argentina. Other countries have experienced insane inflation since 2016 (Turkey, Lebanon, Iran, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Angola, Haiti, Yemen, Syria, Sri Lanka, Suriname…) but wouldn’t qualify as technical hyperinflation.