The Online Safety Bill is Insane

With the world's attention on the Russell Brand scandal, a far more sinister law has just been passed through Parliament to curtail freedom online and give more power to Ofcom

“If I may transact with you only by the good graces of those watching above, then I am something below. I am a subject. I am not a man, but a child. But is a child even an appropriate metaphor? Children are generally loved by their parents. Do you feel similarly loved by [intelligence agencies]? Farm animals, perhaps, is a better metaphor.”

The recent accusations against Russell Brand have caused a media furore. In Channel 4’s programme, Dispatches, he was accused of sexual assault, rape, manipulation and grooming between 2006 and 2013. Brand may very well be guilty of the accusations that are being levied against him, but if he is innocent it won’t matter because he is already being tried by the court of public opinion rather than an appropriate judicial process. YouTube has already demonetised his channel, depriving him of a significant income source estimated to be in the region of £1m/year, his tour and Netflix show have both been cancelled, and all this without Brand even having had the chance to defend himself.

However, whilst Brand’s situation may have garnered a lot of media attention, a new law was quietly passed in the UK that deserves a far greater degree of scrutiny and public outcry, as it effects all of us. The Bill has passed through the House of Commons and the House of Lords, and now awaits the Royal Assent.

The Online Safety Bill has the goal of “making the UK the safest place in the world to be online”. Ofcom, our national ministry of censorship and Karens, would be granted even more censorious powers under the new law; if Ofcom were to deem that certain content is inappropriate, they would have the powers to fine those who produced and obligate social media platforms to remove it.

The Bill was first proposed under Theresa May’s government, during which time the Home Secretary Sajid Javid boasted that it would mean Britain had “the toughest Internet laws in the world”. A peculiar brag, when one considers the “toughness” of Internet laws in Russia, China and North Korea.

The case for more safeguarding

A key focus of the Bill is that Britons should be able to access the Internet as safely as possible. In particular, there has been a focus on protecting children online from paedophiles and other such nefarious actors.

Of course, we all want to live in a world where effective measures are being taken against paedophiles, but one shouldn’t be surprised that bad actors would use such a pretext to duplicitously usher in more dystopian policies that curb civil liberties.

Despite the safeguarding narrative, the Bill is not only designed to protect children, but also to protect adults from what could be perceived as harmful. Do we really need the state to “protect” us? Has it done a good job of protecting us over the last few years?

Moreover, laws that restrict Internet access in such a way are not a panacea for such crime — far from it. Any criminal with an IQ above 80 knows perfectly well how to use Tor with VPNs to circumvent the regulations anyway. These restrictions wouldn’t deter those who are intent on being criminal, but would instead remove the protections that law-abiding members of society ought to expect.

Censorship since 2020

Since 2020, there has been a noticeable rise in the rate of censorship online. Personally, I have had two Twitter accounts banned without recourse (once in 2020 for mocking lockdowns, then again in 2021 for mocking the vaccine rollout), and I am not a well-known public figure. Many public figures, such as the cardiologist Aseem Malhotra, were censored from social media platforms after speaking out about the risks that the vaccinations posed. This created a dangerous precedent in which The Science wasn’t scientific in a way that anyone would normally understand it, but rather the result of government diktat.

Podcasters and content producers who spoke out against approved narratives either had their podcasts removed from major platforms, or had their content accompanied with labels that link back to sources sharing approved narratives (a more subtle form of discrediting them).

Hardly any British politician has had the confidence and conviction to stick their head above the parapet and speak out against the damage caused by the vaccination programme, despite how incredibly well-documented the chicanery has since become. In fact, much of the government’s Covid-19 inquiry has been focused on why the government didn’t lock down sooner, rather than whether it should have locked down at all. The Pfizer documents, investigated forensically by journalists such as Naomi Wolf, are replete with horror stories and clearly demonstrate an unprecedented scale of criminality and absurd degrees of incompetence (Occam’s razor providing the most charitable explanation). It is now public knowledge that major pharmaceutical manufacturers were granted immunity by the governments that they signed contracts with, and even signed deals that didn’t allow governments to test the batches they received before administering them. Andrew Bridgen, the MP for North West Leicestershire, is one of the few who has tried to bring up the issue in Parliament. Shortly after raising his concerns, he was removed from the Conservative Party and branded an anti-semite. The GB News presenter Mark Steyn, one of the few MSM journalists to publicise with what was abundantly obvious to anyone with any braincells, was fired from his job and fined by Ofcom after interviewing victims of the vaccination programme (including those who had lost loved ones to heart attacks or had to amputate limbs). There are countless other stories of individuals being discredited and censored for not being complicit with the government’s totalitarian enforcement regime.

The trend of excommunication from society hasn’t only been a part of our social squares. After Nigel Farage was recently de-banked from Coutts and Natwest (and refused a bank account at a plethora of other banks), he brought the scandal to the public attention and has since been campaigning to change banking laws so that PEPs cannot be treated unfairly. The extent to which individual sovereignty has been eroded by the banking sector, and the complicity of government regulators in this debacle, has been absurd: former Chancellor the Exchequer Nigel Lawson revealed that his granddaughter, who suffers from Down’s Syndrome, was refused a bank account because of the alleged “money laundering risks”. Since this debacle, scores of people have come to the fore to share their stories about how they have been denied access to basic banking services thanks to the nature of being PEPs (of which there are over 90,000 in the UK alone). A report released yesterday by the FCA denied that there was any evidence whatsoever that any politician had ever lost their bank account because of their political views — a total farce. What’s most concerning is that banks don’t even have to provide you with a reason for freezing or closing your account: in 2019 Barclays froze my account for nine months without providing a reason, and the unceremoniously reopened it — I never found out why.

The 77th brigade

Laura Dodsworth’s book State of Fear outlines the various ways in which the British state attempted to scare people in into compliance, as well as to discredit and censor those who opposed the official government narrative — a difficult job given that The Science was unscientific and changed daily: at one time sex was banned with someone in another household, but was permissible if outside in a group of up to six.

One of the most concerning aspects of this is the 77th Brigade. According to Big Brother Watch, the 77th Brigade is a part of the British army that is focused on “audience analysis [and] disseminating counter-propaganda”, and is known for having previously conducted successful operations against Al-Quaeda and the Taliban.

The UK Chief of Defence Staff, Sir Nick Carter, announced in 2020 that 77th Brigade was being used to counter Covid-19 “disinformation” and would be supporting the government’s Rapid Response Unit in doing so. Once this was revealed, there was some concern that British soldiers were being deployed against British citizens themselves, but the Ministry of Defence stated that “The military do not and have never conducted any kind of action against British citizens,” and that they were instead focused on countering hostile intentions from abroad. This was a lie. Big Brother Watch discovered from a FOI request that in order to understand the “cognitive behaviours of audiences, actors and adversaries”, the 77th Brigade passed a plethora of information to the Cabinet Office, including claims that “the UK government [had] threatened, manipulated and deliberately terrified” Britons — all of which was true. Names, Tweets, and other personal information were handed to the Cabinet Office, and all bar one of the cases “were clearly identifiable as UK-based”. In other words, the British army collaborated with the government to suppress and counter accurate information because the government didn’t approve of opposition.

Insofar as it pertains to the new legislation, do we really think that further removing culpability for unelected, lying, totalitarians, who have demonstrably enacted a series of psychological operations against their own countrymen, ought to be granted greater powers?

“The safest place in the world to be online”

One of the most insane mantras surrounding the implementation of the Bill has been the notion that Britain should have the safest Internet in the world.

Adults, as well as children, would be “protected” from being exposed to offence. Jimmy Carr is one of the UK’s most successful comedians, and although his style can be controversial, he commands a large following and is very popular. Many of his jokes are designed to shock his audience, in the same way that much of comedy plays with that which is inappropriate and would not be acceptable outside the context of stand up comedy. In particular, some of his jokes about the holocaust on his Netflix special caused a stir, and Nadine Dorries, who was serving as the Culture Secretary from 2021-2022, stated that under the legislation his content could be removed from the Internet and television. Whilst talking to Times Radio, she said:

“We don’t have the ability now, legally, to hold Netflix to account for streaming [Jimmy Carr’s Netflix special], but very shortly we will.”

We live in a society where the populous is cucked by the fatal conceit of believing that the government serves their interests. The state is not some divine protector sent from on high, but a protection racket that holds elections; despite what behavioural psychologists at the Nudge Unit and SPI-B may believe, we are not subjects to be shepherded, controlled and manipulated. We should not require permission to speak with and transact with one another. Our government is supposed to serve the citizenry, not to dictate and mollycoddle.

The WEF and similar laws in Europe

Unsurprisingly, the World Economic Forum believes that these censorious ideas are brilliant. They have previously boasted that by 2030, nobody will have any privacy and that this will lead to a far more utopian world.

The WEF has taken a very proactive approach to ushering in similar policies in other countries around the world. Once again using the pretext of safeguarding children, the WEF successfully lobbied the European Union to approve the Digital Safety Act last year. Companies that are found not to be compliant could face fines of up to 6% of their global turnover.

The DSA requires social media platforms to be held accountable for fake news, Russian propaganda, targeted adverts, and all criminal activity. Whilst most of this seems positive and well-intentioned, it once again begs the questions as to what constitutes “fake news”, thus providing a carte blanche for regulators to attack those whom they disagree with.

Dame Caroline Dinenage believes herself to be judge, jury and executioner

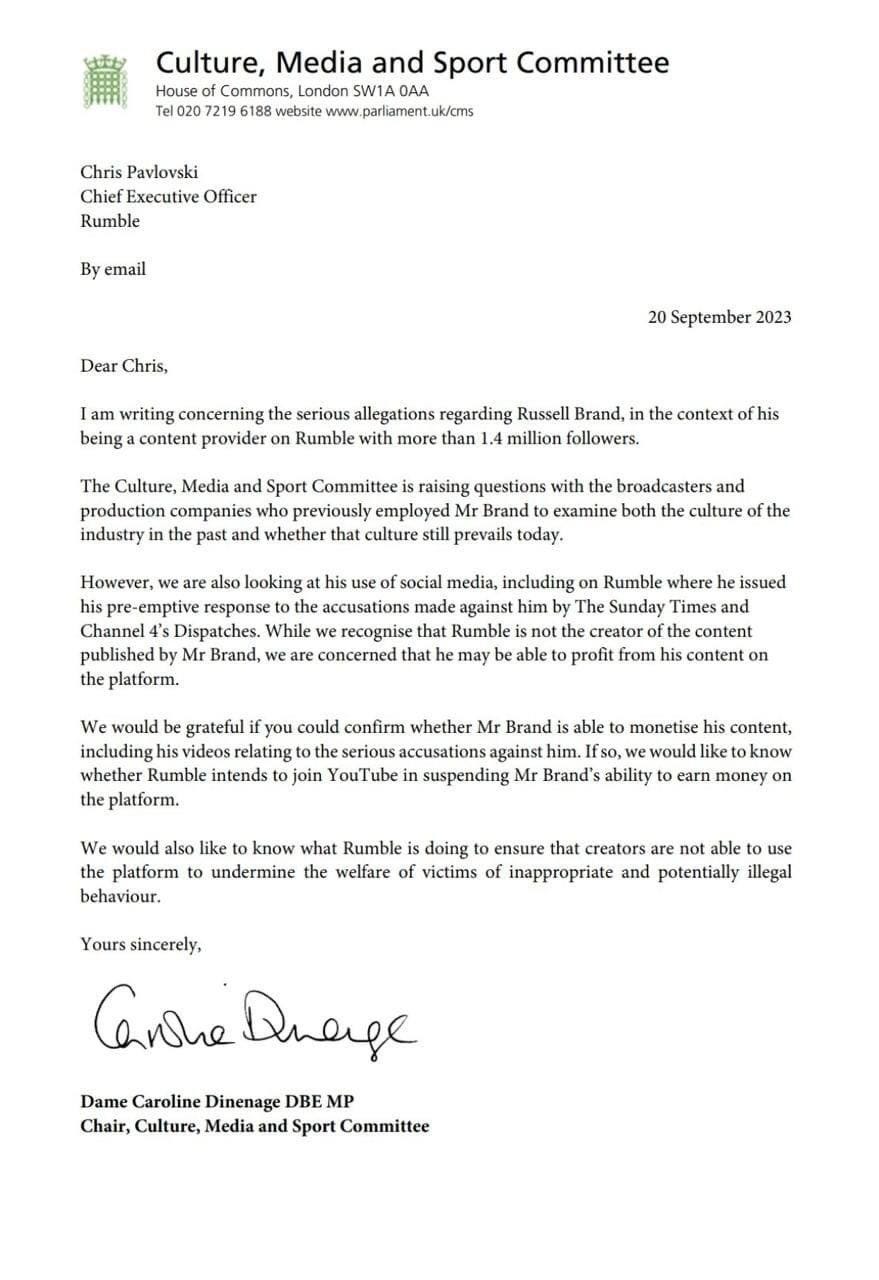

Whilst Brand still hasn’t been charged (let alone prosecuted) for any wrongdoing, this hasn’t stopped our authoritarian political class from assuming the role of judge, jury and executioner. Dame Caroline Dinenage, who is currently serving at the Chair of the Committee for Culture, Media and Sport, wrote a letter to Chris Pavlovksi, the CEO of Rumble.

Although she doesn’t explicitly ask Pavlovksi to demonetise Brand, the implication is clear that she fully expects him to do so.

Pavlovksi responded to her request by making it clear that none of Brand’s content would be removed from Rumble and none of it would be demonetised:

"We regard it as deeply inappropriate and dangerous that the UK Parliament would attempt to control who is allowed to speak on our platform or to earn a living from doing so. Singling out an individual and demanding his ban is even more disturbing given the absence of any connection between the allegations and his content on Rumble.”

Unfortunately, the subjective wording of the new Online Safety Bill means that even if Brand isn’t convicted of any wrongdoing, his career could still be destroyed with the stroke of a pen. According to the Free Speech Union:

“The Online Safety Bill is a censors’ charter … A major shortcoming of the Bill is that it creates a new legal duty to protect adults from content which is lawful but might cause “harm”. Social media companies would be obliged to remove content that is legal but, in some way, “psychologically harmful” (to adults, not just children). That would mean speech that is lawful offline would become prohibited online, with social media companies facing heavy fines from Ofcom if they failed to remove it. This would inevitably lead to Google, Facebook and Twitter removing vast swathes of lawful content, either voluntarily or at the behest of politically motivated complainants claiming to speak on behalf of vulnerable groups.”

Circumventing the state’s lack of moral authority

Hobbes took the view that one should always surrender to the whims of the state, because the stability and structure that it can offer is far better than living a life that is “nasty, brutish and short”. Many dominant figures of The Establishment are willing to conform and acquiesce to onerous legislation that serves little purpose in practice other than to kibosh those who hold views that aren’t deemed politically palatable.

Nevertheless, we ought not forget that the state does not have the moral authority to disrespect its citizens and to treat them like cattle. We should not respect laws that are unjust, particularly when the rationale is so obviously biased. Our speech should not be suppressed just because someone might deem it potentially unpalatable.

If Sunak decided tomorrow that mask mandates should return, that vaccinations should be mandated, that lockdowns should return, or that its better to live in a society where people are prosecuted based on accusations alone, we have a moral imperative to reject these laws.

Fortunately, insofar as it pertains to the digital world, we can fight back against a lot of these issues. Decentralised social networks such as Nostr are gaining popularity, as are new platforms for publications such as Mirror. The UI/UX may not be as good as Twitter or Substack, but that won’t always be the case.

If individuals can’t defend themselves from the rising wave of censorship on centrally-controlled platforms, then they will inevitably opt to use different platforms entirely. In such a scenario, it really won’t matter what Ofcom tries to legislate. If Big Brother tries to control what we can say and see on Facebook, YouTube and Twitter, they may end up inadvertently and irreparably damaging these companies with their unintended consequences. Of course, we shouldn’t expect that Our Great Leaders to have factored in such a scenario, for they are too myopic and if the last few years showed us anything: they aren’t that bright.